The 13 biggest fundraising mistakes start ups make

Bonus post: This month we have a special guest post by Matt Ward. Matt is a serial entrepreneur, growth marketer and ex-VC podcaster turned startup & business coach that helps mission-driven businesses change the world faster. He’s built and sold 3 companies (incl. a 7-figure eCommerce exit in under 12 months), coached thousands of startups & brands through his eCommerce & tech-focused podcasts. With so many experiences to share, let’s see what Matt has to say about fundraising.

📔 LESSONS OF THE WEEK

The 13 biggest fundraising mistakes start-ups make 😵

Fundraising is one of the most important aspects of any venture-scale startup. Building something meaningful that takes the world by storm requires serious time and effort – and for that, capital. Because even if you’re willing to hustle, developers and founders can’t live off Ramen and equity forever.

And while not every startup can (or should) consider external/venture funding, the vast majority of companies looking to transform the world could profit tremendously from a bit of outside capital – at least if they go about it in the right way.

The problem is, fundraising is sexy. How many TechCrunch articles have you seen lauding XYZ’s latest $100M round. Now compare that with stories about the scrappy, bootstrapped startups…

Sure the allure of funding—both from a PR and a personal ego perspective (because we all want to be “better” than our contemporaries) as well as its ability to be rocket fuel for your business—can be massive, funding can also cause massive problems and major headaches for founders.

Because fundraising is hard.

Because not all investors are created equal.

Because you don’t have the first idea how to raise money, or when, or from whom?

If you are a first-time founder, even the thought of fundraising can be totally overwhelming. Who would seriously give you hundreds of thousands (if not millions of dollars) for “imaginary” equity in your business…? How can you convince them it’s worth it?

The stakes have truly never been higher.

The good news is, most founders make more or less the same mistakes. And since you are here reading this article, you might just be able to avoid the biggest blunders.

Which just might save your startup. So let’s get started.

1. Fundraising too soon

Every startup starts with an idea – a problem, a back of the envelope calculation, maybe even a half-functional prototype. Something makes you think you might just be an entrepreneur and might just want to build this “idea” into a business. Maybe you’re even going to “change the world” or invent the greatest thing since sliced bread.

Whatever it is, there is one critical thing to keep in mind:

Ideas are worthless. Execution is everything.

Think about that for a second. Pause, soak it up. It’s important to realise your idea means nothing. Your plan to sell recyclable shoes, create an all-natural sugar alternative, automate tax accounting or create the next Uber for ocean freight isn’t a business. It isn’t even unique. In fact, almost every single idea you ever have has been thought of by someone else at some point in time.

Because no one else before you managed to make that idea a reality. Instead, it remained what it always was – a flitting thought in someone’s head. Because ideas without action are meaningless.

So, let me ask you again: why would any investor pay to own part of nothing? Think about that. Would you pay someone for a great idea for a business?

Not if you’ve ever built your own business. Because then you’d know how hard it is. You’d know that the “killer idea” is only the first in a series of millions of steps that goes into creating a business of any value or meaning.

Because you don’t have traction.

Because you haven’t proven it yet.

You need to be “ready” for funding when you go to investors. You need leverage to negotiate, and the earlier you are in the company’s development, the more you are going to have to give up.

So, when is the ideal time to look for funding? Good question. It comes down to a variety of factors like what’s the status of your product, project and team, is this your first rodeo, what kind of track record do you have and how big is the overall opportunity/market you are tackling?

As a rule of thumb, first-time founders should consider fundraising only after they’ve built a decent prototype or MVP. Once there is something tangible and you’ve put some “skin in the game,” investors are much more likely to take you seriously and offer fair(er) terms.

That said, generally, the longer you can delay raising money (assuming you don’t need the money – either because you’re profitable or can self-fund the business), the better. Would you rather give up 30% when a month of coding and hustling later, it’d have only cost you 10%?

2. Starting fundraising too late

Ironically, the second biggest mistake founders make (especially after completing their first friends & family or pre-seed round) is taking too long to start fundraising.

You’ve started to build your business, are beginning to see traction and are racing ahead at a relentless pace, working all hours of the day and night. Things are moving, maybe you’ve even hired a few people – you’re going a million miles a minute.

Why stop and waste your time focusing on fundraising? A pitch deck, a few quick emails and you’ll have a couple of term sheets in no time, right?

Wrong.

Regardless of how things are going, fundraising is always a brutal slog. Everything takes longer than you’d think. Even if you have traction, even if you’re building something world-changing.

Because you’re asking investors to part with money.

And they’re getting hundreds of pitch decks a week.

Truthfully, it is hard enough to stand out and get a meeting, let alone a term sheet.

Unfortunately, it is often a numbers game – because breaking through the noise is never guaranteed. Even Uber, Airbnb and Facebook were passed up by the majority of VCs.

This means even if you’re a hot startup, your chances of getting a meeting might be only ten or twenty percent. And then, there’s getting a second meeting. And then, a terms sheet.

It’s all about tons of cold outreach and leveraging connections. And it takes time. To perfect your pitch deck, to find the perfect investors and then to actually go through the whole process. Add due diligence and put together the full round, and in general, I recommend startups budget a solid 6 months for fundraising. That means, if you’ve got 9 months of runway, you better start planning your next raise pretty soon.

Because if you’re too late, you’ll either run out of money, have to cut headcount or be forced to compromise on investors/terms… none of which bodes well.

3. Not raising enough money

Right along with starting your fundraise too late is failing to raise enough to reach the next milestone. Eighteen months of the runway is a good rule of thumb. It gives you enough dry powder to go “heads-down” for a solid year before having to think about fundraising again.

Because the only thing harder than building a game-changing business is doing it while having to stop for fundraising every 3-6 months.

So, wouldn’t it make sense just to take more money then?

Wrong again!

4. Raising too much money

On the flip side to raising too little, is raising too much and you might be surprised to know it is even more common and often more devastating than underfunding your company.

Because the worst thing that can happen to any founder is to be so diluted as to basically become an “employee” in your own business. Not only is it incredibly demotivating not to have upside, but it also cripples your company’s chance to raise in the future because no investor wants an unmotivated founder.

In general, every round is about 20% dilution and I’d almost never recommend doing more than 30% unless it’s a merger, acquisition or the last funding you’ll ever need. Otherwise, you’re just setting yourself up for trouble.

Especially if your valuation is too ambitious.

5. Optimizing for valuation

Valuations aren’t only for determining ownership/dilution and keeping score on Crunchbase. They are supposed to be a measure of your company’s progress and future potential.

But what happens when you fail to live up to those lofty goals? What happens when you’re so successful as a child Hollywood star or a first-time author that anything you do afterwards would struggle to live up to your previous accomplishments or expectations?

The same paradox applies to startup valuations. Many a startup have been hamstrung, if not downright destroyed, by overly ambitious valuations.

Because when Blue Apron’s Series D was $135M at a $2B valuation (which assumed certain lofty milestones), who wants to invest in their less-than-stellar public stock with a market cap of just $179M (8.95% off its high!),

And when your existing investors (who have information rights and know what’s going on with the company) decide not to follow on (because otherwise, they’d need to mark down their investment, and thus, their ROI and carry – for more on investor economic dynamics, see this post), what does that say to other prospective investors.

We call that negative signalling, kind of like a chef that won’t eat his own cooking.

6. Not optimizing for smart money investors

There is money, and then there is smart money. You know that already. Some investors have great track records, teams and networks that open doors or even portfolio companies who’d be perfect customers for your product. Or maybe it’s tactical advice, help with marketing, a background in legal or HR…

Whatever it is, some investors bring serious value to the table while the majority are nothing more than a piggy bank.

And trust me, I know how tempting it can be as a startup founder who has raised initial friends and family round to take the easy money. All you want is to get back to building your business and hitting your milestones.

But having the wrong investors can backfire – like when you need follow-on funding or a bridge round and Uncle Bob’s out of cash and the no-name VC you raised from goes belly up, won’t follow-on or doesn’t have those great Series A connections they boasted about.

(For more on the subject, here’s more on the pros & cons of various classes of investors.)

7. Taking money from the wrong investors

Worse even than “dumb money” are investors or LPs with a negative image. While money is great, taking money from unsavoury folks can literally cripple your business.

Because who you work with says a lot about the values of your company.

And this same caution applies to less “sinister” sources as well, like corporate venture funds.

Imagine building a plant-based meat business with a slaughterhouse as a major investor, a sustainable fashion brand funded by Big Oil or an encryption company backed by the Kremlin… Your customers need to trust your credibility. That means walking the walk.

Time horizons can be problematic as well. If you’re building a business with plans to change the world and eventually go public, a high-frequency hedge fund might not be your best bet. If your timeframe isn’t aligned with your investors’ goals, they can make your life a living hell.

The good news is, most VC funds operate on a 10-year fund cycle (with an additional two years of optionality). That means they’re expecting a liquidity event (acquisition or IPO) within a maximum of 12 years (so they can distribute to their LPs). Contrast that with Wall Street funds expecting an ROI every single minute/second and you’ll see where things could go south real fast.

GENERAL NOTE: Every VC fund claims they’re “founder-friendly” and will be incredibly helpful in growing your business. Don’t trust them. If you want the real story of who to trust and who to work with, ask around and see what their portfolio companies have to say – off the record, of course.

8. Fundraising for a business that’s not venture scaleable

The economics of venture capital is very straightforward – VCs only care about outliers. One out of every ten or so investments should pay for the others many times over, and generally speaking, investors target companies with a 50 or 100x potential (to make up for all the flops).

If you’re going to take VC money, you need to know the expectations and the strings attached. All of which means, most companies aren’t suitable for venture capital.

How many mom & pop coffee shops or web dev firms do you know that could realistically 100x their operations and output? Almost none. Because those businesses are not ultra-scalable – they require manual labour (and often capital and/or space).

That’s why Uber and Airbnb were so innovative (although Airbnb is a better business in my opinion) – the world’s largest taxi and hotel companies that don’t own a single taxi or hotel. Instead, they facilitate everything with software (which can be scaled almost infinitely and updated constantly at almost no cost) and have almost no capital costs.

That said, sometimes VCs will still give you money, even if your business isn’t venture scale (or shouldn’t be). That’s what happened with Rent the Runway and Casper mattress, where investors pile money into businesses that simply don’t have the unit economics and cost structure to scale profitably.

Unfortunately, this is often the case with physical products or other business models that lack built-in flywheels (more on designing viral loops here) or winner-take-all dynamics.

So be careful.

Because if you take that investor money, your dreams of building a “4-hour workweek” or lifestyle business just went out the window.

9. Fundraising on bad terms (not just valuation)

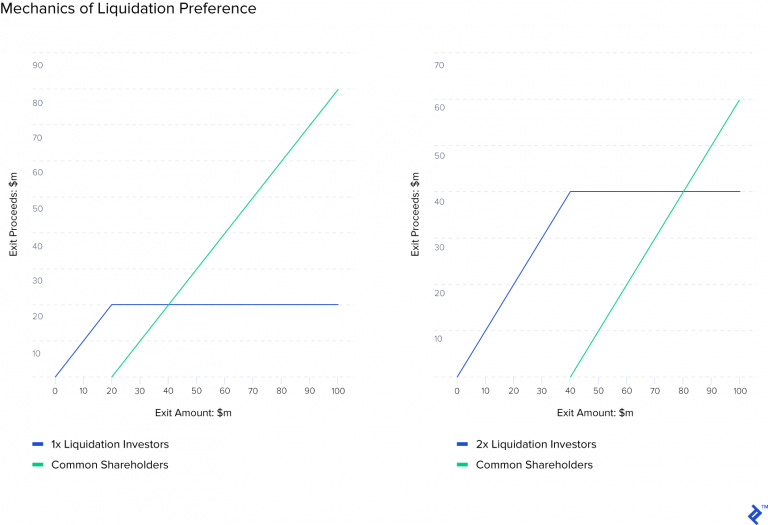

The terms of a venture financing round are often even more important than the valuation itself. It doesn’t matter if you raised $20M at an $80M pre if you gave up “double-dip” preferred shares or too many board seats.

NOTE: Double-dip preferred refers to 2X preferred liquidation preferences. That means, if you sell your company, your investors get at least double their money back before you ever see a dime. See graph below from Toptal to see what this looks like in practice.

As you can see, if you ended up having to sell the business for $40M or less, you as the founder (whose blood, sweat and tears built the business) would get nothing.

And there are plenty of other term sheet pitfalls founders need to be wary of, which Toptal cover pretty well in a blog post here.

10. Overpromising or outright lying

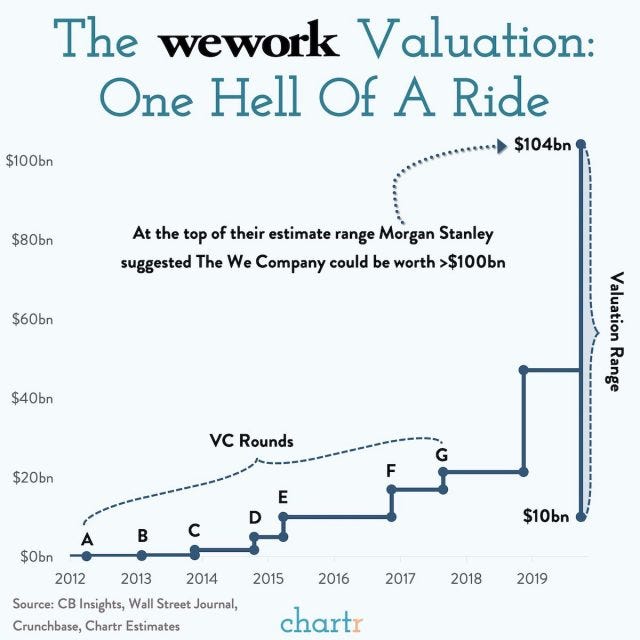

There is a difference between Elizabeth Holmes fraudulent claims that Theranos could run full blood diagnostics from only a drop of blood and WeWork’s Adam Neumann, who’s hyped up claims and borderline insanity led WeWork to grow to a $47B private valuation (of course, led by SoftBank) before it came crashing to Earth.

And while neither is good, in the wake of the implosion from each, Holmes is now on trial for fraud and may well see jail time while Neumann got a $1.7B golden parachute pension – which is just horrific considering how he treated employees, who ended up with essentially nothing.

So, rule #1 when it comes to fundraising, DO NOT LIE. It can only come back to bite you, especially as any VC worth their salt will diligence your company before making the final investment. And nothing looks worse than inflated (or outright false) pitch deck stats that don’t hold up to scrutiny. Especially because word gets around.

But overpromising can be just as damaging. Seems counterintuitive? If anything, aren’t the best founders also the most visionary, i.e. the ones shooting for the stars? How can Tesla’s promised ship dates and autopilot functionality be anything other than overpromising?

Here’s the thing: a) you’re not Elon Musk and b) there is a difference between promising something and aiming for something. Every investor knows your targets are ambitious and there’s a very real chance you don’t hit them.

But you need to be at least in the ballpark. Otherwise, when it comes time to raise your next round, if you haven’t hit your milestones, you may well be looking at a bridge round or a down round – neither of which look great for the trajectory of your supposed “rocket ship.”

11. Not sending investors updates

What is the easy way to grow your business and acquire new customers… It’s a trick question. Why acquire new customers when it’s so much easier to upsell your existing ones? That’s why maintaining a good rapport with your investor base is so critical.

Odds are, you’re going to need more money at some point… and most investors have more money. That’s why the fastest way of filling your next round is simply wowing your existing investors so much that they throw money at you rather than risk other investors coming in and taking a piece of the pie.

That’s where investor updates come in. The more consistently and openly you communicate with them, the better. They already know, like and trust you, all you need to do is prove you’re worth continuing to invest in. And most investors follow on, at least their pro-rata – except when you’re clearly underperforming, inconsistent or hard to work with.

Investor updates allow you to ask for help, connections, etc… by simply updating your investors monthly (at the very least quarterly) with the latest happenings and traction in the business.

They’ll appreciate it and it will keep you honest and accountable as you constantly have to evaluate and summarize your progress, goals and future plans.

TAKE AWAY: Update your investors with a brief email once a month.

12. Not following up with investors

Most investors are just as busy as you are. That means, emails occasionally get missed and things fall through the cracks – so follow up with every investor if you haven’t heard from them in a while. You never know what might happen.

It’s also a good idea to follow up after your pitch, thank them for their time and ask if they have any additional questions.

But following up is pretty straightforward and this has been an incredibly long article already, so I’ll leave it at that.

13. Not practising your pitch or having automatic answers to investor questions

After creating a killer pitch deck, nothing is more important than practising your pitch. Because it is not natural to ask for money. The truth is, everything about the process of fundraising is a bit foreign until you’ve done it a few times.

That’s why, even after you’ve practised dozens of times in the mirror and with your mom, your kids, or your husband, it’s still a good idea to target lower-tier investors first. This is your shot after all and you wouldn’t want to blow it with your dream Series A firm by “going in cold.”

So, stack ranks your prospective funds in order of potential: low, medium and high. Then, as you practice your pitch with the less promising prospects, you’ll learn how they react, what kind of questions they ask, where they get excited or confused and what kind of feedback do they give – all of which is gold when it comes to reworking your deck and prepping for your perfect pitch.

Because let’s face it, no one’s perfect the first time.

PRO TIP: Make a list of all the possible objections an investor could have that would prevent them from investing in your company and make sure you have great, off-the-cuff answers ready. Nothing impresses investors more than a founder that’s prepared and done their homework.

PRO TIP 2: Know a thing or two about the investor and firm you’re pitching before making your pitch. Sometimes, knowing they personally scouted eBay, founded Pinterest or were early at Google can make the difference between clicking and coming up flat.

Closing Thoughts on Fundraising

Fundraising is a process, a sales process of finding prospects and selling them on the future potential of your business. That’s it. Don’t get overly excited or nervous. Come prepared, avoid the pitfalls listed above and you’re already ahead of the majority of startups anyway.

Just do your thing and sell your vision and keep hustling. If you start your fundraising process early enough and stick with it, you’ll maximize your chances of success.

But after thinking about fundraising for the past 3000+ words, there’s one even more important thing to keep in mind.

Ideas are worthless. Execution is everything.

Because if your product is incredible and your traction is exploding, fundraising will take care of itself.

Want help with your fundraising strategy or perfecting your pitch or pitch deck? That’s what I’m here for – say hi.